Adapted from Setting the Standard for Project Based Learning: A Proven Approach to Rigorous Classroom Instruction, by John Larmer, John Mergendoller, Suzie Boss (ASCD 2015). This post is also available as a downloadable article.

It’s encouraging that Project Based Learning has become popular, but popularity can bring problems. Here at PBLWorks, we’re concerned that the recent upsurge of interest in PBL will lead to wide variation in the quality of project design and classroom implementation.

If done well, PBL yields great results. But if PBL is not done well, two problems are likely to arise. First, we will see a lot of assignments and activities that are labeled as “projects” but which are not rigorous PBL, and student learning will suffer. Or, we will see projects backfire on underprepared teachers and result in wasted time, frustration, and failure to understand the possibilities of PBL. In either scenario, PBL runs the risk of becoming another one of yesterday’s educational fads – vaguely remembered and rarely practiced.

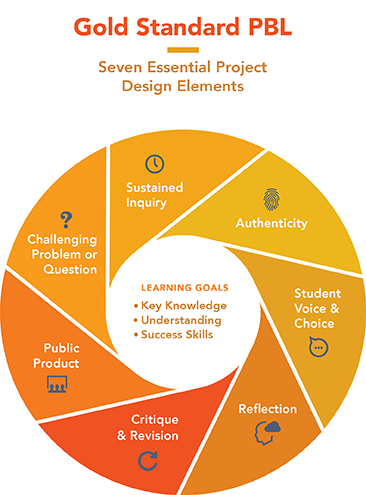

So, in order to help teachers do PBL well, we created a comprehensive, research-informed model for PBL – a “gold standard” to help teachers, schools, and organizations to measure, calibrate, and improve their practice. This term is used in many industries and fields to indicate the highest quality process or product. Our conception of Gold Standard PBL has three parts: 1. Student Learning Goals (in the center of the diagram) 2. Essential Project Design Elements (shown in the seven sections of the diagram), and 3. Project Based Teaching Practices (which we explain elsewhere).

Student Learning Goals

Student learning of academic content and skill development are at the center of any well-designed project. Like the lens of a camera, our diagram puts the focus of PBL on preparing students for successful school and life experiences.

Key Knowledge and Understanding

Gold Standard PBL teaches students the important content standards, concepts, and in-depth understandings that are fundamental to school subject areas and academic disciplines. In good projects, students learn how to apply knowledge to the real world, and use it to solve problems, answer complex questions, and create high-quality products.

Key Success Skills

Content knowledge and conceptual understanding, by themselves, are not enough in today’s world. In school and college, in the modern workplace, as citizens and in their lives generally, people need to be able to think critically and solve problems, work well with others, and communicate effectively. We could add other skills to the list, such as creativity/innovation and project management. We call these kinds of competencies “success skills.” They are also known as “21st Century Skills” or “College and Career Readiness Skills" and are often seen in "Graduate Profiles" created by schools and districts.

It’s important to note that success skills can only be taught through the acquisition of content knowledge and understanding. For example, students don’t learn critical thinking skills in the abstract, isolated from subject matter; they gain them by thinking critically about math, science, history, English, career/tech subjects, the arts, and so on.

We recommend projects include a focus on one or two success skills specifically, even as others are being gained, since it's impossible to teach and assess every skill in every project--then teachers can emphasize other skills in other projects. Projects may also help build habits of mind and work and personal qualities (such as perseverance, growth mindset, or compassion), based on what teachers, schools, parents and communities value.

Essential Project Design Elements

So what goes into a successful project? Based on an extensive literature review and the distilled experience of the many educators we have worked with over the past fifteen years, we believe the following Essential Project Design Elements outline what is necessary for a successful project that maximizes student learning and engagement

CHALLENGING PROBLEM OR QUESTION

Open-ended questions and challenges give students a purpose for learning and cause them to stretch their thinking muscles. Developing solutions requires them to apply new knowledge.

The heart of a project – what it is “about,” if one were to sum it up – is a problem to investigate and solve, or a question to explore and answer. It could be concrete (the school needs to do a better job of recycling waste) or abstract (deciding if and when war is justified). An engaging problem or question makes learning more meaningful for students. They are not just gaining knowledge to remember it; they are learning because they have a real need to know something, so they can use this knowledge to solve a problem or answer a question that matters to them. The problem or question should challenge students without being intimidating. When teachers design and conduct a project, we suggest they (sometimes with students) write the central problem or question in the form of an open-ended, student-friendly “driving question” that focuses their task, like a thesis focuses an essay (e.g., “How can we improve our school’s recycling system, so we can reduce waste?” or “Should the U.S. have fought the Vietnam War?”).